OLD TESTAMENT: 1 Samuel 16:1-13

To read the Old Testament Lectionary passage, click here

The books of 1 and 2 Samuel witness to one of the must crucial periods of transition and change in the story of ancient Israel. At its opening, Israel is sort of a loose federation of tribes and at the end of the second Book of Samuel, there is an emerging monarchy firmly in place under David. Originally, the books were one book. The oldest Hebrew manuscript includes both on a single scroll. The division may have been introduced by later Greek translators (the Septuagint) just to make the manuscripts a more manageable size. The division did not appear until the fifteenth century.

The passage that we read, the anointing of David, sets David out as “God’s choice”. So the human actions that are depicted represent the carrying out of a Divine plan. The account of David’s anointing by the prophet Samuel was probably placed as an introduction to the history of David’s rise to power. The key theme, although it is translated in many ways, means “to see”, making that an emphasis of the passage—to see what God has done. As God’s anointed one, David becomes God’s agent and prophet who can then be anointed, rejected, or confirmed. Once again, we are reminded of the unlikely vessels of God’s grace. God’s choice is David, a shepherd, an eighth son (eighth connoting the “next thing”, a new beginning), from the village of Bethlehem, from a family that has no obvious pedigree. It reminds us that God finds possibilities for grace in the most unexpected places. This is the way that God lays the hope for a new future. This is the way that God calls us to a “faithful seeing”. This passage shows us that God calls ordinary people to do extraordinary things. This passage includes the warning against looking only at appearances. That is part of that “faithful seeing”—to look past the obvious.

There’s another unlikely one here, though. What about Samuel? God called him to go to Jesse the Bethlehemite and anoint a new king. Well, I’m pretty sure that Saul would not have been impressed with that had he found out. What if Samuel had just said, “You know, God, I would really rather not. That just doesn’t work into my plan.”?

In this Lenten season, what would change about our journey if we knew where we would end up, if we thought that we might end up in a place that we didn’t plan? And what would change about our life if we knew how it was all going to turn out? I mean, think about it…the boy David is out in the field just minding his own business and doing what probably generations of family members before him had done. He sees his brothers go inside one by one, probably wandering what in the world is going on. Finally, he is called in. “You’re the one!” “What do you mean I’m the one?” he probably thought. “What in the world are you talking about? Don’t I even get a choice?” “Not so much.” And so David was anointed. “You’re the one!”

What would have happened if David has just turned and walked away? Well, I’m pretty sure that God would have found someone else, but the road would have turned away from where it was. It would have been a good road, a life-filled road, a road that would have gotten us where we needed to be. But it wouldn’t have been the road that God envisioned it to be.

We know how it all turned out. David started out by playing the supposed evil out of Saul with his lyre. He ultimately became a great king (with several bumps along the way!) and generations later, a child was brought forth into the world, descended from David. The child grew and became himself anointed—this time not for lyre-playing or kingship but as Messiah, as Savior, as Emmanuel, God-Incarnate. And in turn, God then anoints the ones who are to fall in line. “You’re the one”.

Do we even get a choice, you ask? Sure, you get a choice. You can close yourself off and try your best to hold on to what is really not yours anyway or you can walk forward into life as the one anointed to build the specific part of God’s Kingdom that is yours. We are all called to different roads in different ways. But the calling is specifically yours. And in the midst of it, there is a choice between death and life. Is there a choice? Not so much! Seeing the way to walk is not necessary about seeing where the road is going. So just keep walking and enjoy the scenery along the way!

- a. What is your response to this passage?

- b. What does the idea of the signs of God’s grace appearing in unlikely vessels mean for you?

- c. Why is that difficult for us to see?

NEW TESTAMENT: Ephesians 5:8-14

To read the Lectionary Epistle passage, click here

Most scholars agree that this letter was not written by Paul, but rather pseudonymously by one of his disciples or students. For the writer of this letter, the focus of God’s mystery is not the cosmic Christ, as it is for Paul, but the church as the “body of Christ”. So there’s lots of “body” language in the letter—Christ as head, church as body. Ephesians often refers to believers as “saints” and tends to focus on being holy and blameless as a body in order to unite with Christ (the head).

The passage that we read contains an insistence that there is a separation between “children of light” and “those who are disobedient”. There is a more dualistic nature to the writings than many of Paul’s actual writings. (Light vs. Dark) Ephesians may anticipate that Christians will be active moral agents in the world. But that is not limited to our own conduct. Rather we should move beyond refusal to participate in evil and expose evil deeds around us. It is another focus on “enlightened or faithful seeing”.

This passage essentially contends that to “walk in the light” means that we are no longer naïve. It is not about being happy or “blessed” in terms of how this world sees “blessed”. The world is illumined by our faith. We now must own a commitment to justice and compassion for all of Creation. Light is goodness and justice and truth. It is not about merely living a moral and righteous life; it is about witnessing to the light that is Christ. Light and darkness cannot exist together. As the passage says, light makes all things visible and then all things visible become light. The Light of Christ makes that on which is shines light itself. The passage exhorts us to wake up and see the light and then live as children of that light; in essence, we are called to become light.

William Sloane Coffin said this is in his book The Heart Is a Little to the Left:

[There is much talk] about “traditional values” and “family values.” Almost always these values relate to personal rather than social morality. For [many people] have trouble not only seeing love as the core value of personal life but even more trouble seeing love as the core value of our communal life—the love that lies on the far side of justice. Without question, family responsibility, hard work, compassion, kindness, religious piety—all these individual virtues are of enduring importance. But again, personal morality doesn’t threaten the status quo. Furthermore, public good doesn’t automatically follow from private virtue. A person’s moral character, sterling though it may be, is insufficient to serve the cause of justice, which is to challenge the status quo, to try to make what’s legal more moral, to speak truth to power, and to take personal or concerted action against evil, whether in personal or systemic form….

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, a mentor to so many of my generation, constantly contended that in a free society “some are guilty but all are responsible.”…Jesus subverted the conventional religious wisdom of his time. I think we have to do the same. The answer to bad evangelism is not no evangelism but good evangelism; and good evangelism is not proselytizing but witnessing, bearing witness to “the light that shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it”; bearing witness to the love that burns in every heart, deny it or suppress it as we will; and bearing witness to our version of the truth just as the other side witnesses to its version of the truth—for let’s face it, truth in its pure essence eludes us all. (William Sloane Coffin, The Heart is a Little to the Left, p. 17-18, 19, 24-25.)

- a. What meaning does this passage hold for you?

- b. How does this speak to the way our world looks at “morals” and “morality” today?

- c. What does that mean for us personally?

GOSPEL: John 9:1-41(9:1-12)

To read the Lectionary Gospel passage, click here

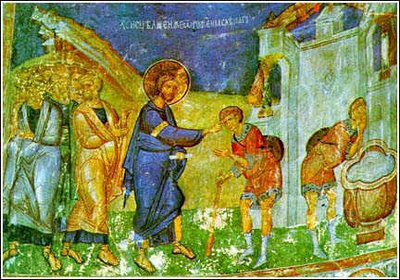

This entire lectionary passage contains the healing miracle and then is followed by dialogue and some interrogation about that miracle. The opening of the passage contains some more language about darkness and light, night and day as well as the depiction of Jesus as the “light of the world”. This plays right into the healing miracle in which Jesus brings sight to someone who had none. In essence, Jesus is bringing light to one who had only darkness.

The Pool of Siloam from our Gospel passage was located just beyond the city walls of Jerusalem. It was actually the only permanent water source of the city during the first century, fed by the waters of the Gihon Spring which was diverted through the rather complex water system in Hezekiah’s Tunnel, which was built in the 8th century BCE. You’ll also see it referred to as the Pool of Shelah or the waters of Shiloah. It was outside the city gates so this man, who, in essence, would have been considered unclean, could wash there but it was near enough to the city gates that the water could have been carried into the temple.

It’s interesting that the first thing that people address here is sin. The man has been apparently blind from birth and their first thought is sin? Did he commit the sin? What an odd question! Was he supposed to have committed some sin in the womb that was apparently terrible enough to blind him for life? Or did his parents sin? It’s an odd line of questioning to us. They see a man that has missed out on so much of what life holds, that has never seen what you and I take for granted every day, and they immediately want to know what he did wrong or what his parents did wrong to deserve that. But Jesus doesn’t see a sinner; Jesus sees a child of God.

And so he reaches down into the cool dirt and picks up a piece of the earth. He then spits into his hand and lovingly works the concoction into a sort of paste. And then, it says, he spreads the mud into the man’s eyes and tells him to go wash in the Pool of Siloam. And the man’s eyes were opened and he saw what had been always hidden from his view.

The healing power of clay (or mud) was a popular element of healing in the Greco-Roman world. But the “making of mud” in this passage is what causes Jesus some problems. The act of “kneading” (as in bread or, in this case, clay) was explicitly forbidden on the Sabbath. So, it was not the act of healing that prompted the questions but, rather, the preparation for it. The man was apparently fully attentive to who Jesus was and what had happened. The fact that in v. 12 the man claims not to know where Jesus is draws attention to Jesus’ absence in the following dialogue.

Most of us probably don’t have a good idea of even why this was this way. Sabbath, or Shabbat, as we know, is supposed to be a day of rest, a remembrance of the seventh day of Creation when God rested, blessed this day, and made it holy. But we need to be clear here that “resting” did not really mean that God lay down and took a little nap; rather, God ceased creating. And we are called to do the same. Sabbath is not a calling to “rest”, per se; it is a calling to cease creating, a calling to quit trying to be God, to let God be God.

So this kneading, this taking dirt and saliva and making mud was, in effect, creating. And they were right! Jesus was creating—he was creating mud, he was creating sight, he was creating life. No one could really prove or disprove what had happened. This man just saw in a way that he had not before. The obstacle proved to be not his disability but the fact that the ones who considered themselves the most righteous were blind to him and to the possibility that God had acted in his life.

Once again, there is a certain dualism in the story. The children of the light are those that see Jesus and know him; the children of darkness do not. Here, too, there is a sort of “spiritual blindness”, those who cannot see Jesus for what he is but are instead wrapped up in seeing the world.

Also included in this story is the attempt by some to link disability with sin and Jesus’ clear rejection of that. It is that idea of God’s punishment of those who are bad or who have done something wrong. It is interesting, too, that this sheds a commentary on the “rules” of religion. This is from a sermon by Richard Lischer:

In a church I served, one of the pillars of the congregation stopped by my office just before services to tell me he’d been “born again.” “You’ve been what?” I asked. “I visited my brother-in-law’s church, the Running River of Life Tabernacle, and I don’t know what it was, but something happened and I’m born again.” “You can’t be born again,” I said, “you’re a Lutheran. You are the chairman of the board of trustees.”

He was brimming with joy, but I was sulking. Why? Because spiritual renewal is wonderful as long as it occurs within acceptable, usually mainline, channels and does not threaten my understanding of God. (From “Acknowledgment”, a sermon by Richard Lischer, available at http://www.religion-online.org/showarticle.asp?title=604, accessed 27 February, 2008._

Lischer also points out that the healing of the man takes two verses; the controversy surrounding it takes thirty-nine. That’s pretty interesting.

At the end of this passage, Jesus says, “I came into this world for judgment so that those who do not see may see, and those who do see may become blind.” This season of Lent is as much about showing us our blindness, our darkness, as it is about bringing us light. For that is the way we see as God sees. It is a way of seeing anew, seeing beauty we’ve never seen before, seeing the Way of Christ. Rainer Maria Rilke said that “the work of the eyes is done. Go now and do the heart-work on the images imprisoned within you.” That is the work of Lent—to release us from our spiritual blindness, from our old way of seeing, frozen in time, and to light the way for a vision of eternity.

- a. What meaning does this passage hold for you?

- b. How would you define “spiritual perfectionism” or “spiritual blindness” in this story and in today’s world?

- c. We tend to view this as a “miracle” or a “healing” story. How does it change if we view it as a commentary on our own lives?

Some Quotes for Further Reflection:

The desire to fulfill the purpose for which we were created is a gift from God. (A. W. Tozer)

Turn your face to the light and the shadows will fall behind you. (Maori Proverb)

It is because we have at the present moment everybody claiming the right of conscience without going through any discipline whatsoever that there is so much untruth being delivered to a bewildered world. (Mohandas K. Gandhi)

Closing

O my Beloved, you are my shepherd, I shall not want; You bring me to green pastures for rest and lead me beside still waters renewing my spirit. You restore my soul. You lead me in the path of goodness to follow Love’s way. Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow and of death, I am not afraid; For You are ever with me; your rod and your staff they guide me, they give me strength and comfort. You prepare a table before me in the presence of all my fears; you bless me with oil, my cup overflows. Surely goodness and mercy will follow me all the days of my life; and I shall dwell in the heart of the Beloved forever. Amen. (from “Psalm 23”, in Psalms for Praying: An Invitation to Wholeness, Nan C. Merrill, p. 40)

OLD TESTAMENT: Genesis 12:1-4a

OLD TESTAMENT: Genesis 12:1-4a