OLD TESTAMENT: Ezekiel 37: 1-14

To read the Old Testament Lectionary passage, click here

Ezekiel was both a prophet and a priest to the Hebrew people during the 6th century BCE, probably beginning before the conquest of Judah and then going into the Babylonian exile. Ezekiel, himself, was actually one of the ones who was exiled, who lost his place of identity and home. His message is clear: he assures his hearers of God’s ever-abiding presence among them, of God’s involvement in what happens in their lives and in the world around them. To these people who had been ejected from their homes and who were now wandering in hopelessness and despair, this was a message of real hope. According to Ezekiel, God would restore their lives.

The first part of the passage we read is Ezekiel’s vision or prophecy; the last part is an interpretation of that vision. The valley here is probably referring to the plains between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, which was a dry and arid place. There is some speculation that this is the site of a battle at some point during this siege. The bones there are dry, brittle, lifeless, and broken. Whether this is meant literally (as in the case of a battlefield) or metaphorically (as in the case of lost homelands), they symbolize the lost hopes and despair of the exiles themselves. For them, the kingdom of Israel is gone. The temple is gone and the city lies in ruins. It is dead and their lives have gone away with it.

And then, according to Ezekiel, “the hand of the Lord came upon me.” In The Message, Eugene Peterson says that “God grabs me”. Think of that image. Here was Ezekiel, probably feeling the weight of despair of those around him and virtual helplessness at what he could do as their leader. But then “God GRABBED him…I have something to show you.” And there in the middle of death and destruction and despair, God showed him what only God could see. And then God breathes life into these bones. The word “breath” here is the Hebrew word, ru’ah. We don’t really have a good translation. It means breath; it also means wind or spirit. It is the very essence of God. And the bones come to life.

The idea of God creating and recreating over and over again is not new to us. But most of us do not this day live in exile. We are at home; we are residing in the place where our identity is claimed. So how can we, then, understand fully this breathing of life into death, this breathing of hope into despair? The image is a beautiful one and yet we sit here breathing just fine. We seldom think of these breaths as the very essence of God. In the hymn, “I’ll Praise My Make While I’ve Breath”, Isaac Watts writes the words, “I’ll praise my God who lends me breath…” Have you ever thought of the notion of God “lending you breath”? Think about it. In the beginning of our being, God lent us breath, ru’ah, the very essence of God. And when our beings become lifeless and hopeless, that breath is there again. And then in death, when all that we know has ended, God breathes life into dry, brittle, lifeless bones yet again. Yes, it is a story of resurrection.

God gave us the ability to breathe and then filled us with the Breath of God. We just have to be willing to breathe. It’s a great Lenten image. It involves inhaling. It also involves exhaling. So exhale, breathe out all of that stuff that does not give you life, all of that stuff that dashes hopes and makes you brittle, all of that stuff that you hold onto so tightly that you cannot reach for God. Most of us sort of live our lives underwater, weighed down by an environment in which we do not belong. We have to have help to breathe, so we add machines and tanks of air. But they eventually run out and we have to leave where we are and swim to the top. And there we can inhale the very essence of God, the life to which we belong. God lends us breath until our lives become one with God and we can breathe forever on our own.

- What meaning does this passage hold for you?

- Do you ever feel like God grabs you?

- What does that image mean to you of God breathing life into death?

- How pertinent do you think this image is to today’s world?

- How faithfully do you think we really believe that God can make all things new? How ready are we to let God breathe new life into us?

NEW TESTAMENT: Romans 8: 6-11

To access the Lectionary Epistle passage, click here

The main theme on the surface of Romans 7 and the first part of Romans 8 is the Jewish Law, the Torah and what it really means to live under God’s law. And for some scholars, the passage that we read lies at the very heart of this section on the Torah. In fact, Romans 8 is said to have been Paul’s greatest masterpiece, the epitome of his work. For us, the passage may almost be TOO familiar. There have been a multitude of prayers that have been created from it and Bach made it the backbone of a whole cantata.

In verse 5, right before our passage, Paul lays out the two ways of living—two mindsets—of the “flesh” and of the “Spirit”. For Paul, of the “flesh” is not as humans but rather a perversion of who we should be as humans. But it is the “way of the Spirit” that brings life. And since, as followers of Christ, the Spirit of Christ dwells in us, we do have life. It is like the Ezekiel passage. If we live in the “way of the Spirit”, the essence of God will be breathed into us and bring us to life. That is the way to true freedom. Here, for Paul, living within the “law”, living within the Spirit, is living within the power of love.

Often the idea of the “mind” is set against the idea of the “Spirit”, as if the two are not compatible existing together. But here Paul admonishes the reader to “set the mind on the Spirit”. For Paul, the “body” (GR. soma) is inherently neutral. It is not “bad”, per se, the way we often try to make it. But without the Spirit, the essence of Life, breathed into it, it remains neutral and ultimately dies. The two belong together. God’s Spirit brings breath and life.

Once again, it is a good Lenten passage. We tend to get wrapped up in those things of the “flesh”—our needs, our desires, our fears. Paul is not saying that we dispense with them as bad. Paul is making the claim that the Spirit can breathe new life into them. There is no sense in fighting to sustain our identity apart and away from God. It will ultimately die. Paul has more of a “big picture” understanding than we usually let him have. He’s saying that the flesh in and of itself is not bad but the Spirit brings it to life. I don’t think he is drawing a dividing line between darkness and light, between mind and Spirit, between death and life; rather, he is claiming that God’s Spirit has the capability of crossing that line, of bringing the two together, infused by the breath of God. It is a spirituality that we need, one that embraces all of life. It is one that embraces the Spirit of Life that is incarnate in this world, even this world. I mean, really, what good would the notion of a disembodied Spirit really do us? Isn’t the whole point that life is breathed into the ordinary, even the mundane, so that it becomes holy and sacred, so that it becomes life?

- What meaning does this passage hold for you?

- What, for you, is the Spirit of God in you?

- What does that mean for our lives?

- What happens when we separate the “mind” and the “Spirit” in our lives?

GOSPEL: John 11: 1-45 (11: 17-44)

To access the Lectionary Gospel passage, click here

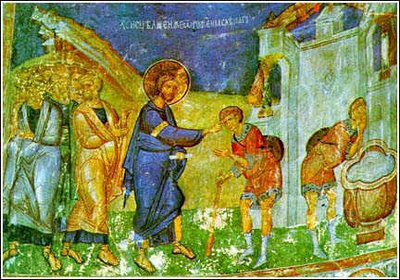

This entire lectionary passage contains the account of the raising of Lazarus. But the bulk of the story is not focused on Lazarus’ raising but rather on the preparations for it. This story is only told in The Gospel According to John, so it is unclear from where the story comes. There is, of course, no way to prove the “facts” of this miracle, but it sets the stage for Jesus’ own raising and what that means for the world. It is important to note that the Jewish understanding was that one’s soul “hovered” around the body for three days, but Lazarus has been dead for four days. In their understanding, his soul was gone; his body was dead, dead, dead.

So the story sets the stage for the beginning of God’s new age. The point is that the way to experience this power over death is to believe. When Jesus asks Martha, ‘Do you believe this?” he asks her to believe both that he is the resurrection and the life and that as the resurrection and the life he defeats the power of death. It means that death is reintegrated as a part of life, rather than a feeble end.

We have probably never been to a funeral that did not include the passage “I am the Resurrection and the Life. He who believes in me, though he die, yet shall he live.” Jesus asked Martha, “Do you believe this?” “Did I not tell you that if you believed, you would see the glory of God?”

For many, this is one of those odd, somewhat problematic texts. After all, people don’t usually get up and walk out of tombs into the land of the living. This story challenges norms and even reality, to some extent. Perhaps that is the point. Perhaps it sort of jolts us into the realization that God is capable of more, that God will go beyond what we plan, what we think, even what we imagine. And yet, “Jesus wept.” In the older translations, it is supposedly the shortest verse in the Bible. Jesus’ tears remind us that grief is real and that God realizes that and truly cares what happens to us.

Ironically, this is the act that would ultimately cost Jesus his life. After this, the Sanhedrin’s step in and the journey to Jerusalem, mock trial and all, escalates. There is no turning back. Perhaps it should be our turn to weep. But we are given a new hope and a new promise. Jesus said, “Unbind him, and let him go.”…He will do the same for us. Even as this was a foreshadowing of the Resurrection, it was also a foretelling of what Jesus would do on the Cross. And the love that Jesus felt for Lazarus foretells that love for humanity that took Jesus to the Cross.

This is a good Lenten story. It is the story about the in-between. Some things don’t make sense. Some things don’t go like we plan. Creation groans towards its ultimate promise. And so we wait…and we believe.

Until recently, I have seen this story of the raising of Lazarus as an inaccessible and, in some respects, unappealing story. Lazarus is not fleshed out as a character. All we know about him is that Jesus loved him and he got sick and died. His sisters, whom we have met in Luke’s gospel, seem a little passive aggressive. Their initial note doesn’t ask Jesus to come. It just informs him of their brother’s illness. Then, when he approaches their town, they each, separately, run out and lay the identical guilt trip on him. “Lord, if you had been here, our brother would not have died.” As for Jesus, he is never more certain about the panoramic big picture than here. Lazarus’ illness will not end in death, and it will be for the glory of the Son of God. He is, at the same time, seldom more disturbed by the sights and sounds of a specific scene: the sound of mourners wailing and the stench of death.

So for many years, I have read this text and thought hmm, this is odd. And read on. So much for true confessions. This past week, I have had an epiphany. It is probably one you the reader have already had, and if so, I apologize in advance for pointing out what has long been obvious to you. The epiphany is that we are to see ourselves in Lazarus and see the miracle of his restoration of physical life as the beginning of our entry into eternal life that begins the moment we accept Jesus’ offer of relationship with us.

The sequence of the Gospel of John is the opposite of the children’s game “Show and Tell.” It is “Tell and Show.” The Prologue tells us that Jesus is the light and life of the world (Jn. 1:4, 5). The giving of sight to the man born blind (Jn. 9) and the raising of Lazarus from the dead (Jn. 11) show us Jesus giving light and life to particular human beings. We are invited to see ourselves in them and him in our lives. We are to see ourselves in Lazarus, whose name, a shortened form of Eleazar, means “God helps.” He is from a town whose name, Bethany, means “House of Affliction.” So God helps one who suffers from affliction. John takes a friendship between Jesus and this family and an event that has the quality of reminiscence and shapes it to his theological purpose (Brown, 431). Lazarus is the “one Jesus loves”; he represents all those whom Jesus loves, which includes you and me and all humankind. This story, then, is the story of our coming to life from death in this present moment, not just in a future event.

The Fourth Gospel repeatedly uses the physical realm as a metaphorical pointer to the spiritual realm. Water is a metaphor for the quenching of our spiritual thirst through Jesus’ presence; Jesus is the living water (Jn. 4:14). The bread Jesus multiplies to feed the crowd is a metaphor for the satisfaction of our spiritual hunger that Jesus brings; Jesus is the Bread from Heaven (Jn. 6:35). Sight is a metaphor for the spiritual vision and clarity that Jesus brings; Jesus is the light of the world (Jn. 8:12, and chapter 9 where Jesus gives sight to a man born blind). Here, in chapter 11, the restoration of physical life is a metaphor for breaking free from the bonds of spiritual death into the gift of eternal life that Jesus brings. Jesus is the resurrection and the life (Jn. 11:25-6: “I am the resurrection and the life. Those who believe in me, even though they die, will live, and everyone who lives and believes in me will never die.”). (“Lazarus is Us: Reflections on John 11: 1-45”, by Alyce M. McKenzie, available at http://www.patheos.com/Resources/Additional-Resources/Lazarus-Is-Us-Alcye-McKenzie-04-04-2011.html, accessed 5 April, 2011.)

- What meaning does this passage hold for you?

- What does the image of Jesus weeping mean for you?

- What, for you, is the Spirit of God in you?

- What does it mean to truly say that we believe the words “I am the Resurrection and the Life”?

Some Quotes for Further Reflection:

For death begins at life’s first breath; and life begins at touch of death. (John Oxenham, a.k.a. William Arthur Dunkerley, (1852-1941))

Meaning does not come to us in finished form, ready-made; it must be found, created, received, constructed. We grow our way toward it.(Ann Bedford Ulanov)

The way of Love is the way of the Cross, and it is only through the cross that we come to the Resurrection.(Malcolm Muggeridge)

Closing

Out of the depths I cry to You! In your Mercy, hear my voice! Let your ears be attentive to the voice of my supplications! If You should number the times we stray from You, O Beloved, who could face You? Yet You are ever-ready to forgive, that we might be healed. I wait for You, my soul waits, and in your Word, I hope; My soul awaits the Beloved as one awaits the birth of a child, or as one awaits the fulfillment of their destiny. O sons and daughters of the Light, welcome the Heart of your heart! Then you will climb the Sacred Mountain of Truth; You will know mercy and love in abundance. Then will your transgressions be forgiven and redeemed. Amen.(from “Psalm 130”, in Psalms for Praying: An Invitation to Wholeness, Nan C. Merrill, p. 278)