FIRST LESSON: Acts 5: 27-32

During the Season of Eastertide, our first readings are not from the Old Testament but rather the Book of Acts—the beginnings of the believers’ story after the Resurrection. All of a sudden this seemingly bumbling and clueless band of disciples that had followed Jesus around all through the Gospels suddenly seems to “get it”. But remember, too, that earlier in Acts (our Pentecost story), the Holy Spirit had come upon them. They were not alone but were empowered by faith in the Resurrected Christ. They were, in effect, becoming the church. Walter Brueggemann writes that “in the Book of Acts the church is a restless, transformative agent at work for emancipation and well-being in the world.” (April 9, 2007, available at http://theolog.org/2007/04/brueggemann-sermon-starter.html.)

Now they feel compelled to speak the Truth as they see it, even when the act of speaking the Truth is a dangerous one. They speak of Jesus as one in the same as the One and only Lord, God Almighty. And obeying and speaking this truth is above all human authority. Peter and the apostles understood that with the Resurrection of Christ, they were to look to new leadership. They were to follow Christ, rather than the political and religious leaders that were in place in the society.

Now it is important to not begin to fall into this account as one religion against another. This is NOT the Christians vs. the Jews the way some of our Christian brothers and sisters may try to make it. In fact, “Christianity”, per se is essentially a movement within the established faith. Peter is speaking here with the “authority of our ancestors”. He is speaking from the tradition of his people—his Jewish people. Think of it more as a “family feud” or a difference in belief. The words “to Israel” are important. This is not the beginnings of a religious war between two opposing faiths. Here, both sides were convinced that their truth was THE Truth. But it is not unlike our own setting with our own internal struggles between conservative and progressive, traditional and contemporary, right and left, or whatever designations you care to use to fill in the blanks.

Here, Peter was a witness. We know the end of the story. He and others are martyred for their belief. But the important part is that Peter was a witness, doing what all of us are called to do as followers of Christ.

I think it’s important to note, though, that being a “witness” does not call one to be mean-spirited or to wound others who do not think the same way in the process. Peter and the disciples still viewed themselves as part of those to whom they were speaking. They were not pulling away; they were not dismissing them as “wrong” or “evil” or anything else. They were trying to open the conversation of faith. But, of course, they were having to do it with authorities that had the upper hand.

There are those that will see the Scripture as a call to “war” between the so-called “secular humanists” and (I would say) so-called “people of faith”. J. Michael Krech says this in response to that:

[Some people] will see as heir to Peter’s boldness the public high school valedictorian who inserts a prayer into her speech at graduation, despite being warned by the school principal not to do so, thus obeying God rather than human authority. Other Christians will see as closer to the spirit of Peter the protesters whose placards and chants of “No War for Oil” break up a congressional committee hearing on Department of Defense appropriations.

In nations where governments are fairly chosen by the will of the people and orderly processes exist to hear grievances, it may be appropriate that the protesters who interrupt a congressional committee’s proceedings be removed from the room. In nations where the constitution and national heritage encourage mutual respect for people of various faiths and those who hold no religious faith at all, the school principal is correct. Praying your prayer to a captive audience at a public school graduation is not an act of courage but of bad manners…

When [one] speaks with the boldness of Peter and the other apostles, it does, at least over time, encourage hearers to take principled if unpopular stands in the workplace and helps lead us all to be seekers of truth and agents of reconciliation. (J. Michael Krech, in Feasting on the Word, David L. Bartlett and Barbara Brown Taylor, eds. “Second Sunday of Easter”, p. 381, 383.)

- What is your response to this passage?

- Our new United Methodist vows of membership themselves call us to vow our “prayers, our presence, our gifts, our service, and our witness”. What does that mean to you to be called as a witness?

- Why is that so difficult in today’s society?

- What does it mean that we are called to be “transformative agents”, as Brueggemann said?

NEW TESTAMENT: Revelation 1: 4-8

To read the passage from Revelation

This passage is the beginning of what was essentially a formal letter for that time and two-thirds of our passage for this week is essentially the salutation for that letter. The writer named John begins by wishing his readers grace and peace from God. He describes God as “the One who is”, sort of like the Old Testament tradition of God interpreting God’s own name as “I am who I am.” The “one who is and who is to come” presents the timelessness, the eternity, of God. It also speaks to that “already and not yet” characteristic of the Kingdom of God.

The number “seven” (used here for the cities and for the spirits) is intended to mean perfect or complete. The seven churches are named later in this collection known as the Book of Revelation, but it is possible that at the beginning, he was representing all the churches of western Asia minor (modern-day Turkey). Perhaps the writer is trying to depict a God that is beyond what we can imagine, beyond the limits of one human. And once again, we have the depiction of God as the ruler over all, one in our midst, always with us, guiding us. So, in the beginning—God, in the end—God, and throughout it all—God. God’s presence and power transcend all human notions of time. And Jesus Christ, the third figure named in the greeting, is also presented with three corresponding titles—the “faithful witness” (in his ministry, death and resurrection), the “firstborn of the dead” (vanquishing death), and “the ruler of the kings of the earth” (a new sovereignty on the earth.)

Remember that this Revelation was written at least a generation or two after Jesus’ death and Resurrection. The Christian faith was already solidified. And once again, the passage draws to the witness of that faith. There was a definite disparity for those early believers between being “Easter people” and living in the realities of what was often a harsh and cruel world. They were being persecuted and they needed a way to make sense of their faith. Revelation was written to encourage those Christians who were struggling to have faith in light of everything around them when evil seemed to be the only thing at work in the world. It was intended to bring a vision of hope to those whose only way to be “safe in their faith” was to abandon it altogether.

And for those of us who have left the beauty and glory that was Easter morning, with the more than full sanctuary, the beautiful flower arrangements, the “Hallelujah Chorus”, and the high-church celebration, now what? We are not persecuted for our faith, but it is indeed hard. It is hard to stay faithful when there are so many things that tug at your life. And, how in the world do we follow that exhibition on Easter morning? How do we top that? What next?

To understand Revelation for our day, we have to understand the nature of hope. For Christians hope is not a wish. It is not a tooth under a pillow, or fingers crossed or just one more Publisher’s Clearinghouse Sweepstakes try. Hope for a Christian is an assurance, a firm and binding promise. It is a sure thing. Hope is not a feeling. It is a fact. It is a fact rooted in the reality of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ and assured by the amazing, steadfast, unshakable love of God for God’s people. God will not be shaken. Hope is independent of circumstances and it will never be conquered by evil. Even if hurt seems to be winning, the battle for God has already been won.

Several years ago when I was a pastor in the Denver Colorado area, a colleague of mine told me a story of a friend of hers who was traveling home to Denver on a Sunday afternoon from a conference north along the front range of the Rocky Mountains in Fort Collins. The conference had been a good one. The man and the woman were driving home full of what they had learned and talking about how they might use their new learning in their work situations. As they rounded a curve in the road they came upon a serious motorcycle accident. The motorcycle seemed to catch on something and flip into the air. The driver, without a helmet, was thrown fifty yards or so, and the bike landed not far away.

The two were the first to arrive. The man was driving and pulled off the road just north of the accident. Before he shut off the ignition the woman was out of the car and running to the side of the accident victim. The man stopped another car and sent the occupants for help while he began to try to direct traffic. At one point in the chaos he glanced at the woman. She was crouched next to the unconscious young man, stroking his hair and talking to him.

When the ambulance arrived and the young man was whisked away, the man and the woman got back into their car in silence. There was blood on the woman’s hands and around the hem of her skirt.

After a moment, the man said, “I saw you talking to that young man. He was obviously unconscious. He may even have been dead. What could you possibly have been saying to him?”

“I just told him over and over,” she replied, “I just told him, the worst is over. The healing has already begun.”

To those long ago hurting ones to whom John wrote, to those long ago ones whose lives were marked by pain and fear, by weakness and oppression of injustice and death, whose lives were marked by the terror of the now and haunted by the past and uncertain of the future, to those ones and to us, to you, God through the words of Revelation offers us a vision of a brand new life; a life lived in a brand new order in a brand new way. Maybe the images in Revelation are frightening and confusing to you, serpents and lakes of fire, but what is that to us? What God has to say in this letter is that no matter what comes against you in this life; no matter if all of the power of pain and chaos of the universe seems to overtake you all at once; no matter if you can not control one single thing or fix one single thing in your life, the worst is over, the healing has already begun. The lamb is on the throne. Come Lord Jesus, come. (From “Saltwater Apocalypse”, a sermon by Rev. Eugenia Gamble, November 16, 1997, available at http://day1.org/821-saltwater_apocalypse.)

- What meaning does this passage hold for you?

- What does this passage say about the calling to “witness”?

- What does it mean to embody Christ, to embody Easter, to become “Easter people”?

- In what ways do we understand hope?

GOSPEL: John 20: 19-31

You have to wonder what the disciples were thinking locked behind the door of their house. Were they afraid that they would be next? Were they disillusioned that things had turned out that way? Were they feeling remorse or guilt or shame at the parts that they had played (or not played, as the case may be) in the Passion Play? I suppose it’s possible that they were a little afraid of the rumors that Jesus HAD returned. After all, what would he say to THEM?

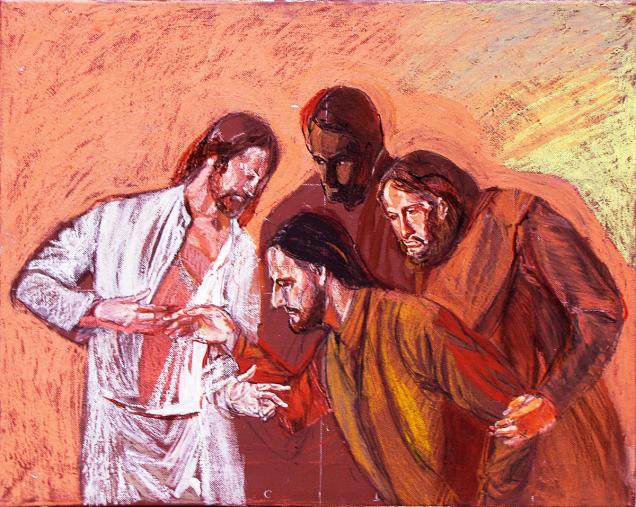

But that’s not what happened. Things were going to be OK. Jesus was back. The disciples rejoiced. Jesus breathed the Holy Spirit into them. They were sent. They became the community of Christ. And so I supposed they went off merrily praising God and being who they were called to be. This is a premise for discipleship. Jesus offered light and truth through his relationship with God. Now the disciples are called to offer light and truth through their relationship with Christ. All except Thomas. Poor Thomas. He wanted to see proof. Why couldn’t he just believe?

On one level, Jesus, with all the grace that Christ offers, gives Thomas exactly what Thomas so desperately needs—proof. Thomas missed his initial opportunity, but Jesus returns. I think we give Thomas a bad wrap—after all, for some reason, he missed what the others had seen. (It is interesting that he was apparently the only one who had ventured outside!) He just wanted the same opportunity—and Jesus gave that to him. He wanted to experience it. The point was that the Resurrection is not a fact to be believed, but an experience to be shared. And perhaps, part of that experience is doubt. Constructive doubt is what forms the questions in us and leads us to search and explore our own faith understanding. It is doubt that compels us to search for greater understanding of who God is and who we are as children of God.

Hans Kung is a Swiss-born theologian and writer. He says it like this: Doubt is the shadow cast by faith. One does not always notice it, but it is always there, though concealed. At any moment it may come into action. There is no mystery of the faith which is immune to doubt. Isn’t that a wonderful thought? Doubt is the shadow cast by faith. Faith in the resurrection does not exclude doubt, but takes doubt into itself. It is a matter of being part of this wonderful community of disciples not because God told us to but because our doubts bring us together. Examining our faith involves doubts, it requires us to learn the questions to ask. And it is in the face of doubt that our faith is born. God does not call us to a blind, unexamined faith, accepting all that we see and all that we hear as unquestionable truth; God instead calls us to an illumined doubt, through which we search and journey toward a greater understanding of God.

Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to belief. (Remember that ALL the disciples had seen Jesus. Thomas just wanted a more tangible showing. The only one in John’s Gospel that really saw nothing was the so-called “Beloved Disciple”, who ran to the tomb and saw nothing.) They have the relationship in Christ to which God calls us. They understand the Christian community—you come together and hold on for dear life as you search for a greater understanding of something that will always be a mystery. But what an incredible mystery it is! And we are given the grace to embrace it.

Frederick Buechner preached a sermon on this text entitled “The Seeing Heart”. In it, he reminds us of Thomas’ other name, the “Twin”. It was never really clear why he was called that, but Buechner says that “if you want to know who the other twin is, I can tell you. I am the other twin and, unless I miss my guess, so are you.” He goes on to say this:

I don’t know of any story in the Bible that is easier to imagine ourselves into than this one from John’s Gospel because it is a story about trying to believe in Jesus in a world that is as full of shadows and ambiguities and longings and doubts and glimmers of holiness as the room where the story takes place is and as you and I are inside ourselves…To see Jesus with the heart is to know that in the long run his kind of life is the only life worth living. To see him with the heart is not only to believe in him but little by little to become bearers to each other of his healing life until we become fully healed and whole and alive within ourselves. To see him with the heart is to take heart, to grow true hearts, brave hearts, at last. (“The Seeing Heart”, by Frederic Buechner, in Secrets in the Dark: A Life in Sermons)

- What meaning does this passage hold for you?

- What does doubt mean in your faith life?

- What does community mean in your faith life?

- What is your response to the notion that those who have not seen and yet have come to belief are the Blessed?

- What, then, does it mean to have a “seeing heart”?

Some Quotes for Further Reflection:

I believe in the resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth…and the resurrection of the body…as it was meant to be, the fragmented self made new; so that at the end of time all Creation will be One. Well, maybe I don’t exactly believe it, but I know it, and knowing is what matters…The strange turning of what seemed to be a horrendous No to a glorious Yes is always the message of Easter. (Madeleine L’Engle)

The beginning of wisdom is found in doubting; by doubting we come to the question, and by seeking we may come upon the truth. (Pierre Abelard, 12th century)

But the proclamation of Easter Day is that all is well…In the end, [God’s] will, not ours, is done. Love is the victor. Death is not the end. The end is life. His life and our lives through him, in him. Existence has greater depths of beauty, mystery, and benediction than the wildest visionary has ever dared to dream. Christ our Lord has risen! (Frederick Buechner, “The End is Life”, in Bread and Wine: Readings for Lent and Easter, 292)

Closing

Yours—we gladly attest—is the kingdom, the power, and the glory. Yours—we gladly assert—are the heavens and the earth. It is you who had made all that is, sun, moon, stars, rivers, forests, minerals, birds, beasts, fish—and us. We say, “in your image.” Yours the kingdom and the power and the glory—and then us.

You do not will us to be powerless either, so you endow us with the power to work, to rule, to govern. We reflect you in our working, in our ruling, in our governing. Ours is the chance for justice and/or injustice, for mercy and/or rigor, for peace and/or war. We grow accustomed to our power, sometimes absolutizing, and then we are interrupted by the doxology on which we have bet everything:

Yours is the kingdom, the power, and the glory. And we are glad. Amen. (“On Creation”, by Walter Brueggeman, in Prayers for a Privileged People, p. 165)