FIRST LESSON: Amos 8: 1-12

FIRST LESSON: Amos 8: 1-12

Read the Old Testament passage

The visions in Amos 7 that we read last week condemn the social injustices that were prevalent in the society at the time. The people had, in Amos’ view, forsaken God and were not living out their relationship within the community. Last week’s reading dealt with the third vision and the confrontation between Amaziah and Amos. In Amos 8, the fourth vision pronounces the finality of judgment by Yahweh on Israel. The reason, again, is because they have oppressed the needy. Amos’s vision involves the land, which in this case will suffer a famine for the people of Israel. Essentially, the judgment is in the form of what appears to be divine silence and unbearable darkness on the part of God.

The pronouncement includes a reversal of time and prosperity. The end will be clearly filled with ruin. No longer will the people be prosperous and ignore those who have less. No longer will they neglect and ignore their neighbor.

This is a hard passage. We’re used to reading Scripture and finding messages of hope, forgiveness, and redemption. But this is different. The passage speaks to us and calls us to look at the balance we have in our lives. It shakes our lives up a bit. How much of our lives is about us? How much of our lives is lived with the consideration for others? How much of our lives is focused on God and what God calls us to be? Have we forgotten God? Perhaps this is a message of hope—a “wake-up call” if you will. God does forgive; God does redeem. But God loves us too much to just let us continue down the unbalanced path that we sometimes create for ourselves.

So, we could dismiss this as a misinterpretation of the words of a grace-filled God or we can relegate it to a time gone by. But, maybe, just maybe, we’re actually supposed to pay attention. Maybe it’s the only way that God can waken us out of our prosperity-induced coma and realize that it is us. We are the prosperous ones. We are the ones that are holding that bounteous basket of summer fruit. And we are the ones who are called to respond to the injustices of the world.

Martin Marty says it well. According to him, “You can tell a lot about people by what they hang on their walls. If it’s someone with an office, it gets even more interesting. In my office at the church I serve, I do not have any diplomas hanging. No awards. No trophies or medals either—not that I ever won any. Not even my ordination certificate is on the wall. I figure that if I or anyone else has to look at some framed document to see or remember my orders before God, I’m in trouble.

Among some interesting pictures and sculptures—you’ll have to see them sometime—I have a construction level mounted on the wall. It’s actually very precious to me. A contractor in my congregation named Rudy gave it to me as a symbol of the need to keep life in balance. He knows I have enjoyed construction in the past. So here is this Stanley level from the 1880s, crafted of beautiful cherry wood and brass. There is also, of course, the little bubble inside, which keeps reminding me that I mounted it about 1/8 inch off level.

I can’t be the only one needing balance in my life. Every day something is out of whack in every soul’s scheduling or decision-making. It has to be, given life’s many pressures. This 24-inch chunk of lumber on my wall is my daily conscience check.

Reflecting on this week’s Old Testament reading makes me look at this level with new eyes. I am beginning to think it is staring me in the face not just to highlight my many challenges to the balanced life. (My wife would be happy to point those out to you.) My level from Rudy is also staring at me to point out the dreadful imbalance that exists between the privilege of my own life and the struggling needs of others. Its gorgeous cherry is tipped in my favor and against the favor of so many people who get stepped on by my way of life. And this gap is a lot more than 1/8 inch.

Amos spoke of scales weighted in favor of the well-to-do and of God holding a plumb line to measure crooked lives. I have this level on my wall telling me to get inside the skin of those harmed by my privileged life. I am an unwitting participant in far too much systemic injustice, more than I’d like to believe. Every system, societal practice, purchase and piece of legislation that benefits me at the expense of the dignity of some other human being is wrong.

I remember Tim Wise once saying that there are a whole lot of us who were born on third base yet think we hit a triple. That’s good. Maybe next week I’ll have to put up a picture of a baseball diamond, right next to Rudy’s level. There is space on the wall. (From “Balance and Privilege”, by Martin Marty, in “Theolog: The Blog of The Christian Century”, July 12, 2010, available at http://theolog.org/2010/07/blogging-toward-sunday-balance-and.html)

1) What is your response to this passage?

2) Where do your own discomforts lie with this passage?

3) What is is that causes us to live lives so out of balance?

4) What message of hope do you hear?

5) What response does this call us to make?

NEW TESTAMENT: Colossians 1: 15-28

The first part of this passage is a sort of “hymn”, proclaiming Christ above all things of this world, proclaiming Christ as the very image of God. It is followed by this address to the Colossians.

As Christianity spread beyond the world of Jewish hopes, the acclamation of Jesus as the Christ became more an acclamation that God had made Jesus king in a much broader sense. Christians began to declare that Jesus will be lord of all. He will unite all people, indeed, everything in one single realm of God’s goodness. “Who is the power or rule or beginning”: this means God has enthroned him, but it also affirms that Christ was there from the beginning. This association of ideas is present in the next phrase: “the firstborn from the dead”. It means, he was the first to be raised from the dead and also that he is God’s firstborn son. Traditionally, the firstborn inherited the major power in a household.

In other words, the old messianic hope has now been transformed, so that it affirms Christ’s resurrection as the moment when something new began: Christ was raised from the dead, the first of many to come, but as the first he is also the leader and will bring about the rule or kingdom of God throughout the whole created order of things. God’s fullness chose to live in Christ. On that basis he will seek to bring about peace in the entire universe: peace with God and peace among all peoples and things.

The writer of the letter also mentions the church. The big vision is that the church is the name for what Christ created at his resurrection rather than a small building on some corner of a city. It is wherever God’s goodness comes to rule. These are grand thoughts. They are easily open to abuse. Some have seen the church as destined to control all political power on earth as part of this vision, often with disastrous consequences. But if we allow the abstractions of the poetry to settle and see beneath and beyond them, the vision is really about God’s love through Christ filling the universe, an echo of the notion that the earth shall be filled with the glory of God. It is a vision of reconciliation with God and among people. It also invites us to include in this the whole creation. It is also very confronting of any and all powers which set themselves up as above love and above God, including both political powers and our own ideas and constructs of our religion.

You could read this as if the writer (probably not Paul) was just trying to get his or her readers back to basics, back to what matters. Maybe it was meant to be a reminder of why we’re here at all, why we believe, why we are the church in the first place. What is it that motivates us to stick around, to keep the church going, to work toward that vision that God holds? And maybe it’s a reminder to not let the “ways of churching” get in the way of what we’re really about. Just stick to the purpose. But, first, we have to know what that is. What does it mean to “present everyone mature in Christ”?

In his classic book, The Effective Executive, Peter Drucker tells how purpose-driven living can affect countless lives in a lasting fashion. He tells the story of Nurse Bryan, a not-so-flashy caregiver who kept an entire hospital on track with her eleven-word purpose-driven philosophy. When facing a medical decision, Nurse Bryan always asked the question, “Are we doing the best we can to help this patient?” These eleven words gradually permeated the entire hospital and became its cultural creed known as “Nurse Bryan’s Rule.” That’s because patients on Nurse Bryan’s floor recovered faster. Drucker claims that ten years after her retirement, “Nurse Bryans’s Rule” was still influencing the culture of that hospital. Superiors and subordinates alike were profoundly affected by one common person’s passion for purpose. It was the great motivator that continues to inspire us here today.

Negotiating the twenty-first century is…bumpy for most individuals and churches. That’s because change is coming at us faster than we can digest it. Education is just one of the areas that is being forced to re-examine its traditional assumptions. Take Shop Class for example. It’s a rite of passage many Boomers enjoyed in their junior and high school years. We learned how to spot-weld a tin pan together, turn wood on a lathe, and run a band saw safely. But those days are fading fast. That’s because shop skills are not being demanded on a college level. Employers are not clamoring for skilled tradesmen as much as they are for trained computer technicians.

So what’s happening in the classroom? The same thing that’s happening in our traditional churches. In a nutshell, we must “pick our pain” from two options. Painful scenario one is a choice many churches are opting for. It goes like this: we will keep doing what we have been doing — and work harder. That’s choosing to continue shop class because we’ve always offered shop class. The result of that decision is that we will maintain what’s familiar, reliable, stable, and comfortable. The pain involved is that we will decline and possibly die. That is because we can never create a better past. It’s done and gone.

Pain number two is the decision to go beyond shop class, but remain true to the purpose of education: preparing people for living life. That involves the pain of growth, risk, renewal, and hard work with much criticism. It’s saying that we will exist to educate people. If shop class fulfilled that role for a time, great, but if it’s not relevant anymore, we will change. Not from education, but from how we’ve always done education. We will let purpose drive us, not precedence.

Could that be the great motivator for us as God’s people? Could knowing why we are on the planet be the corrective to keeping us on track? We are going to experience decent folks off track every day — in our families, in our churches…The great motivator for Paul was to see “everyone mature in Christ.” The energy for that work came from Jesus himself. The same motivation and power are offered to us right here, right now. It is “Christ in you, the hope of glory” (From “The Great Motivator”, a sermon by Kirk R. Webster, available at http://www.sermonsuite.com/free.php?i=788026533&key=yrpG5vaokksiAlq8, accessed 11 July, 2013.)

1) What meaning does this passage hold for you?

2) In what ways might this passage be abused?

3) What message does it hold for our society today?

4) It almost sounds trite, but what does it mean to you to put Christ first in your life?

5) What motivates us as believers of God and followers of Jesus Christ?

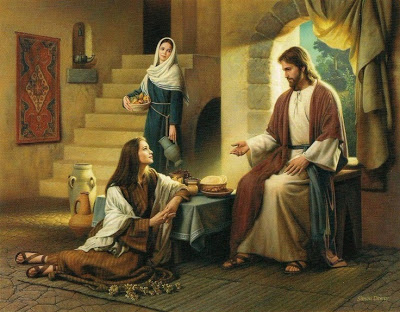

GOSPEL: Luke 10: 38-42

This is a short passage, but probably holds enough to make us a bit uncomfortable. We are forced to think about all the things that we “do” for God. We are forced to look at our busy and too-full lives into which we try to cram as much “good” stuff as we can. And, sadly, many of us experience the same realization that I had: “Damn, I think I’m the sister!”

I personally think Martha gets a bad rap. I mean, after all, she was the one trying to make everyone comfortable, offering “radical” hospitality. And on some level, her sister just let her do all the work and went and sat down and listened to Jesus. But the point is, she LISTENED. She didn’t do for Jesus what she thought he wanted or give to Jesus what she thought he needed. She actually spent time sitting and listening. She opened herself to Jesus himself. The writer is assuming that the most important response is to receive Jesus’ word.

This is probably not meant to be an attack on the “normal” role of hosting guests, just the preoccupation with them. But there’s another side to this. Remember that Martha was acting in the role that society had assigned her. This, too, should be a wake-up call to us. Are there others that we’ve relegated to roles that leave them out of truly being a part of Jesus’ word? Are there others that through our societal or church constructs, we haven’t allowed to enter the conversation? Do we leave room for everyone to live the life that God calls them to live?

I do so want to be Mary. I want to sit at Jesus’ feet and listen to his words. I want to bask in his presence and be a part of who he is. And I want others to feel like they can do the same. But what, pray tell, do we do with all those dirty dishes? Maybe the message is not only about being open to Christ but also about making sure everyone feels free to do the same. The dishes can wait. (But maybe the point is also that we’re all supposed to take part in doing them a little later.) The good news is that Jesus grants permission for all of us distracted, frantic people to sit down and get our fill of Jesus’ word and promise. When we are filled, then we can go to work.

Now, truth be told, if I knew that Jesus Christ, Emmanuel, God-with-Us, the Son of God and Son of Humanity, was coming to dinner, I do think that at least some of my Martha would need to kick in. I would make sure there were fresh flowers and the table would be set with Aunt Doll’s china and I would probably pull out all the stops and make Caramel Macchiato Cheesecake with the homemade caramel sauce that takes so long. And, of course, Maynard the Wonder Dog would have a new bow tie to don. After all, this is Jesus Christ, Emmanuel, God-with-Us, Son of God and Son of Humanity! Shouldn’t we be presenting our best? I mean, surely it’s not appropriate to invite him to your house for a peanut butter and jelly sandwich and put him to work folding laundry to get it off your dining room table so that you can eat! I DO think that’s important. After all, all work is holy if it has the right perspective, the right focus, the right motivator. But, then, after all the preparations were done, I would hope that I could sit and listen and immerse myself in this Holy Presence. I would hope that somehow I could take all the distractions that come to mind and make them holy too. Maybe that’s the whole point—it’s not that what Mary was doing was good and what Martha was doing was bad but rather that somehow, Martha had lost perspective, burying herself begrudgingly in the enslavement of “women’s work” while her flighty sister hob-knobbed with Jesus. What if her preparations were instead focused on creating a feast for a king? What if in her divine work, the presence of God was truly revealed? What if she realized that she was preparing a holy meal?

Maybe her mistake was not being busy but rather missing God in the busyness of everyday life. Maybe she just missed that God shows up in everything that we do and no task is wasteful or menial in the Presence of God. (Or maybe her mistake was not spending the extra 45 minutes to make homemade caramel sauce for the cheesecake!)

“…As Soren Kierkegaard reminds us, ‘Repetition is reality, and is the seriousness of life…repetition is the daily bread which satisfied with benediction.’ Repetition is both as ordinary and necessary as bread and the very stuff of ecstasy…Both laundry and worship are repetitive activities with a potential for tedium, and I hate to admit it, but laundry often seems like the more useful of the tasks. But both are the work that God has given us to do…To convert all our work into prayer and praise is admittedly an ideal, but the contemplatives of the world’s religions might agree that it is something to strive for.” (The Quotidian Mysteries: Laundry, Liturgy, and Women’s Work, by Kathleen Norris, p. 28, 29, 83)

1) What meaning does this passage hold for you?

2) Where do you find yourself in this passage?

3) What distractions exist in your life that pull you into a “Martha” way of being?

4) Who do we “leave out” when it comes to truly experiencing Christ?

5) What would it mean to open everything that we do to God’s Presence?

Some Quotes for Further Reflection:

More than a few Christians might be surprised to learn that the call to be involved in creating justice for the poor is just as essential and non-negotiable within the spiritual life as is Jesus’ commandment to pray and keep our private lives in order. (Ronald Rolheiser, The Holy Longing)

Blessed are the ears which hear God’s whisper and listen not to the murmurs of the world. (Thomas a Kempis)

Just being awake, alert, attentive is no easy matter. I think it is the greatest spiritual challenge that we face. (Diana L. Eck)

Closing

Come and find the quiet center in the crowded life we lead, find the room for hope to enter, find the frame where we are freed. Clear the chaos and the clutter, clear our eyes that we can see all the things that really matter, be at peace and simply be.

Silence…..

Amen.

(Shirley Erena Murray, 1992, The Faith We Sing # 2128)

FIRST LESSON: Amos 7: 7-17

FIRST LESSON: Amos 7: 7-17